Ranavirus micropterus1

Common Name:

Largemouth bass virus (LMBV)

Synonyms and Other Names:

Largemouth bass ranavirus (LMBRaV), Santee-Cooper Ranavirus (SCRV) (group includes LMBV, DFV-16, MFV and GV-6), Ranavirus sp., Micropterus salmoides rhabdovirus (MSRV)

Identification:

The largemouth bass virus is an icosahedral-shaped particle without an envelope. It occurs in the cytoplasm of host fish cells. When it passes out of the plasma membrane of the host fish cell, it acquires an envelope (Plumb et al. 1996).

In Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides), signs of the disease may include increased blood flow and darkened skin, distended abdomen, bloated swim bladder, lesions in the membrane lining the body cavity, necrosis (burst cells resulting in inflammation) of gastrointestinal mucosa, pale liver, red spleen, red intestinal caeca, infected gills, lethargic swimming, decreased responsiveness, swimming at the surface and/or in circles, and difficulty remaining upright. Sores or lesions on the outside of the body are secondary and not caused by the actual viral infection (Zilberg et al. 2000; Goldberg 2002; Brunner 2003; Grizzle and Whelan 2004; Beck et al. 2006).

Size:

LMBV particles are 130 nm from side to side and 145 nm from corner to corner when they are in the cytoplasm of the host cells. After acquiring an envelope they measure 175 nm in maximum dimension

Native Range:

Unknown. LMBV was first identified during an outbreak in the Santee-Cooper Reservoir, South Carolina with a possible earlier outbreak in Lake Weir, Florida. However, this virus is very similar to two fish viruses from southeast Asia (Mao et al. 1999; Plumb et al. 1999) doctor fish virus (DFV) and guppy virus 6 (GV-6) which had previously been isolated in imported aquarium fish (Marschang et al. 2025)

|

|

|

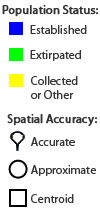

This map only depicts Great Lakes introductions.

|

|

Great Lakes Nonindigenous Occurrences:

LMBV was first detected within the Great Lakes basin in the Bay of Quinte, Lake Ontario in 2000 (Sutherland 2002). That same year, LMBV was detected in Lake George, on the Indiana-Michigan border (Lake Michigan watershed).

Table 1. Great Lakes region nonindigenous occurrences, the earliest and latest observations in each state/province, and the tally and names of HUCs with observations†. Names and dates are hyperlinked to their relevant specimen records. The list of references for all nonindigenous occurrences of Ranavirus micropterus1 are found here.

Table last updated 2/21/2026

† Populations may not be currently present.

Ecology:

HABITAT - This virus was first known only from wild fish and was not reported from hatcheries until 1999 in the southeastern USA. LMBV can affect Largemouth Bass lethally or subclinically (without symptoms), and is particularly prone to infect bass over 30 cm long. LMBV can also infect Smallmouth Bass (Micropterus dolomieui). Bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus), Crappie (Pomoxis spp.), and Chain Pickerel (Esox niger) can be infected, but rarely exhibit clinical symptoms, thus they may serve as disease carriers. Once exposed to LMBV, a population of Largemouth Bass produces antibodies such that subsequent exposures result in less extreme manifestations of the disease. Male fish have a higher resistance to this disease than females as a result of its impact to estrogen-related immune response pathways. Fish kills can be slow and last for several weeks (Goldberg 2002; Woodland et al. 2002; Grizzle and Brunner 2003; Grizzle et al. 2003; Whelan 2004, Dong et al. 2024). | Environmental Tolerance | Value | Source |

| pH (under lab conditions) | 3-9 | Piaskoski et al. 1999; Scott and Aron 2002; Grizzle and Brunner 2003 |

| Minimum viability in water | 3-4 hours | Piaskoski et al. 1999; Scott and Aron 2002; Grizzle and Brunner 2003 |

| Maximum detection in water | 7 days | Piaskoski et al. 1999; Scott and Aron 2002; Grizzle and Brunner 2003 |

| Peak Virulence Temperature | 30°C | Grant et al. 2003; Grizzle and Brunner 2003; McClenahen et al. 2005 |

| 50% Virulence temperature | 17°C | Yang et al. 2024 |

LIFE HISTORY - LMBV can be passed from one infected fish to another, so any practices (such as live wells) that keep infected and uninfected fishes that are in close contact or at high densities can increase transmissions (Grant et al. 2005; Inendino et al. 2005). LMBV can be transmitted through the water and also orally via ingestion of infected animals (Woodland et al. 2002). Transmission from adult to offspring probably does not occur or is very rare (Grizzle and Brunner 2003). LMBV enters cells through the cell membrane, enters lysozymes where it loses its capsule, then the viral DNA enters the cell nucleus where it replicates. Replicated viral DNA exits the nucleus to the cytoplasm where capsules are assembled, and aggregated viral particles are released from the cell through budding (Zhang et al. 2024). Ranavirus can infect almost all tissues and organs but gills, swim bladder and kidneys are particularly susceptible.

Great Lakes Means of Introduction:

The US population likely represents a mutation of GV-6 or DFV introduced with aquarium fish imports (Marschang 2025). Transport of LMBV within North America probably occurs in live wells of fishing boats when infected fish or water are dumped into new habitat or put in contact with uninfected fish, which are then released. Fishing tournaments have been associated with outbreaks, most likely as fish in live wells are both stressed and in close contact (R. Kinnunen Pers. Comm. 2025). Stocking of infected fish could also be a vector.

Great Lakes Status:

Overwintering and reproducing in Lake Erie, Lake Ontario and southern Lake Michigan as well as inland lakes in the southern half of the basin.

Great Lakes Impacts:

Summary of species impacts derived from literature review. Click on an icon to find out more...

| Environmental | Socioeconomic |

|

| | |

LMBV has a high environmental impact in the Great Lakes. As LMBV has resulted in the reduction of native Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) populations, this virus is assessed as having a high environmental impact in the Great Lakes. Further research is needed to determine if a developing immunity similar to the populations seen in Florida is realized in Great Lakes Largemouth Bass populations. In Michigan, LMBV mortality events typically have involved 100-500 fish up to 10 percent of the population per lake (Grizzle and Brunner 2003, Whelan 2004). However, LMBV has also been implicated in several more significant Largemouth Bass die-offs within the Great Lakes basin, (Grizzle and Brunner 2003, Whelan 2004Sarvay 2012).

Symptoms of LMBV can include lethargy, decreased responsiveness, swimming at the surface and or in circles, and difficulty remaining upright (Beck et al. 2006, Goldberg 2002, Grizzle and Brunner 2003, Zilberg et al. 2000). Because of this altered behavior, infected fish may be more susceptible to predation (Lafferty and Morris 1996).

There is little or no evidence to support that LMBV has significant socio-economic impacts in the Great Lakes.

There is little or no evidence to support that LMBV has significant beneficial effects in the Great Lakes.

Management:

Regulations (pertaining to the Great Lakes)

The Great Lakes Fishery Commission lists this species as a restricted pathogen. Screening is required for centrarchids and esocids. Fish exhibiting clinical signs of disease should not be transferred, stocked or released. When detected in the wild, a surveillance program should be initiated and reasonable means employed to prevent spread to new locations.

| Jurisdiction | Regulation | Law | Description | Date Effective |

| Illinois | Other | 515 ILCS 5/20-90 | This species is not on the Illinois Aquatic Life Approved Species List and if it is not otherwise native to Illinois it is illegal to be imported or possessed alive without a permit. & Requires source facilities of any species of live fish, eggs, and sperm to document they are disease free prior to importation | 7/9/2015 |

| Michigan | Other | | Requires imported aquacultured fish to be accompanied by either an official interstate health certificate, official interstate certificate of veterinary inspection, or a fish disease inspection report. Importing aquacultured fish from source facilities with a record of an emergency disease within the past two years is prohibited. Fish imported from non-Michigan source facilities and intended for stocking in public waters must be certified free of LMBV | |

| Ohio | Other | | Requires out-of-state source facilities of live fish to provide health inspection and testing documentation prior to importation | |

| Wisconsin | Other | | Requires source facilities to document fish health inspections prior to importing live fish and eggs (NCRAC 2010) | |

Note: Check federal, state/provincial, and local regulations for the most up-to-date information.

Control

There is no known cure or effective treatment of LMBV infection (Syska et al. 2012). Rapid assays have been developed (Jin et al. 2020, Guo et al. 2022, Jiang et al. 2023, Guang et al. 2024) to support early detection.

Biological

One line of research is exploring options for breeding resistant strains of Largemouth Bass (Li et al. 2024).

Chemical

To prevent spread, disinfection of live wells and other contaminated equipment can be accomplished with a 10% household bleach/water solution (i.e., 100 ml of household bleach to 900 ml of water). Waste water should be discarded away from any water body. Potassium peroxymonosulfate (21.41%), with sodium chloride (1.50%) is another widely available disinfectant (MNR 2012).

Several vaccines are in development (Liu et al. 2023, Fu et al. 2024, Liu et al. 2024, Yi et al. 2024, Luo et al. 2025). A combination of C-120 nanopeptide and anthocyanin has shown promise for mitigating infection (Huo et al. 2024). Multiple compounds are being tested in the laboratory for anti-viral and/or immune boosting properties effective against LMBV including rhein and saikosaponin (Wang et al. 2023, Chen et al. 2024, Li et al. 2024).

Note: Check state/provincial and local regulations for the most up-to-date information regarding permits for control methods. Follow all label instructions.

Remarks:

It is possible that LMBV was first introduced to Largemouth bass populations in Florida in 1991 through contact with imported tropical guppies (Poecilia reticulata) or Doctor Fish (Labroides dimidatus). These two species can harbor nearly identical viruses, known as guppy virus (GV6), and doctor fish virus (DFV), respectively. Given that the technology existed much earlier than the 1990s to detect such a virus and that it was being used to detect other fish diseases, it is unlikely that LMBV was present for many years before 1991.

Spread of LMBV has occurred from Florida through adjacent states, and has only recently reached the Great Lakes drainage. This pattern of spread from Florida could either be due to increased detection efforts in states adjacent to places where recent outbreaks occurred, or to an actual radial spread of the disease. There are a few different strains of this virus present in North America, which suggests either multiple introductions to the continent or that LMBV is not exotic to the continent. More studies need to be carried out to clarify where the virus originated (Mao et al. 1999; Plumb et al. 1999; Goldberg 2002; Grizzle et al. 2002; Goldberg et al. 2003; Grizzle and Brunner 2003). Santee-Cooper Ranavirus (SCRV) is now treated as a species name with LMBV, DFV-16 and GV-6 considered strains within the species (Marschang et al. 2025). Koi ranavirus (KIRV) identified in India may also be a member of this species (Zhao et al. 2023). In older literature LMBV, DFV-16, MFV and GV-6 are treated as individual species. Waltzek et al. (2025) propose renaming this group as Ranavirus micropterus1.

References

(click for full reference list)

Other Resources:

Author:

Kipp, R.M., A.K.Bogdanoff, A. Fusaro, and R. Sturtevant.

Contributing Agencies:

Revision Date:

9/3/2025

Citation for this information:

Kipp, R.M., A.K.Bogdanoff, A. Fusaro, and R. Sturtevant., 2026, Ranavirus micropterus1: U.S. Geological Survey, Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville, FL, and NOAA Great Lakes Aquatic Nonindigenous Species Information System, Ann Arbor, MI, https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/GreatLakes/FactSheet.aspx?NoCache=9%2F16%2F2011+8%3A53%3A17+PM&Species_ID=2657, Revision Date: 9/3/2025, Access Date: 2/21/2026

This information is preliminary or provisional and is subject to revision. It is being provided to meet the need for timely best science. The information has not received final approval by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and is provided on the condition that neither the USGS nor the U.S. Government shall be held liable for any damages resulting from the authorized or unauthorized use of the information.