Stagnicola palustris

(O. F. Müller, 1774)

Common Name:

Marsh pond snail

Synonyms and Other Names:

Piedmont pond snail, Buccinum palustre (O. F. Müller, 1774), Stagnicola neopalustris (F. C. Baker, 1911), Lymnaea palustris (O. F. Müller, 1774)

Identification:

Oblong, conic shell brown to tan in color with transverse lines and longitudinal wrinkles. At least six whorls, and the body whorl is longer than the spire. The animal body is dark, almost black and covered with small black and golden spots. Its tentacles are dark in color and triangular in shape (Say 1821; Hubendick 1951). Stagnicola palustris is anatomically very similar to other Lymnaeidae (of which there are an estimated ~100 species), especially the North American native, Stagnicola elodes, and identification can be difficult without genetic confirmation (Correa et al. 2010; Vinarski 2013).

Size:

Adult average length of 17 mm in temporary habitats and 23 mm in permanent habitats (Brown et al. 1985).

Native Range:

Very wide international palearctic distribution, including much of Europe (from Morocco to Norway). May originate from Eurasia (Correa et al. 2010).

|

|

|

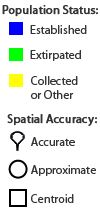

This map only depicts Great Lakes introductions.

|

|

Great Lakes Nonindigenous Occurrences:

Originally, S. palustris was thought to be native to North America and the United States, with a distribution spanning from New England to Oregon and California. As far south as New Mexico (and an isolated area in central Mexico) and as far north as Alaska. Some sources listed S. palustris as native to the Great Lakes region and populations have been recorded in the basin and lakes beginning in the early 1800s. One specimen was even recorded in Lake Superior (Hubendick 1951; Burch and Jung 1988), but has since been re-identified as the North American native, Stagnicola elodes. It is likely most or all of the S. palustris specimens discovered in North America and the Great Lakes are misidentified and it is unknown if S. palustris is truly established the Great Lakes (John Slapcinsky, personal communication, March 30, 2021).

Ecology:

Stagnicola palustris is a simultaneous hermaphroditic, pulmonate snail that inhabits permanent and ephemeral freshwater lakes, swamps, marshes, ponds, and rivers that are rich in organic debris. Chemical habitat requirements are not reported for this species specifically, however, most freshwater gastropods require calcium concentrations above 5 mg/l (Lodge et al. 1987). Further, most snails are not found in waters below a pH of 5 (Jokinen 1983). This species typically has an annual life cycle with semelparous reproduction via self-insemination or outcrossing (Sorenson and Minchella 1998). Egg production ranges from 35 to 330 per female (Brown et al. 1985). The life history traits of S. palustris vary with environmental conditions and habitat type. In very productive (high gross primary production) habitats, S. palustris can have two generations per season (Hunter 1975) and in less productive habitats (such as in northern Canada) it can take several seasons for a single reproduction event due to slower growth and maturity rates (Brown et al. 1985). Further, egg production, growth rate, and size at maturity all increase in productive permanent habitats. However, S. palustris in densely populated ephemeral habits have the greatest reproductive rates as the temporary nature of the pond favors early maturity and high fecundity (Eisenberg 1966; Brown et al. 1985). Juveniles overwinter in cracks in mud surrounding permanent water bodies or aestivate in temporary ones - emerging in late spring to reproduce. In rare circumstances, adults will overwinter by forming diaphragms and covering their apertures (Jokinen 1978; Brown 1979). The diet of S. palustris consists mainly of periphyton and the tissue of living macrophytes (Calow 1970). Carrion is also consumed (Brown 1982). Stagnicola palustris is consumed by waterfowl and crayfish. Its larvae and eggs are eaten by mudminnows (Umbra limi) and sciomyzid flies (Eckblad 1973; Swanson and Meyer 1977; Brown and DeVries 1985; Hanson et al. 1990).

Means of Introduction:

Unknown or natural dispersion.

Status:

Cryptogenic colonizer. Reproducing and overwintering at self-sustaining levels have been recorded in Lake Erie, Lake Ontario, Lake Huron, and Lake Michigan.

Great Lakes Impacts:

There is little or no evidence to support that Stagnicola palustris has significant environmental impacts in the Great Lakes. Stagnicola palustris is an intermediate host for various parasites (Novobilsky et al. 2013; Gordy and Hanington 2019). Notably, lymnaeids are known to transmit Fasciola hepatica, which cause the disease fascioliasis. Fascioliasis can severely reduce the productive capacity of some mammals, particularly deer and livestock (e.g., meat and milk) (Hurtrez-Bousses et al. 2001).

Stagnicola palustris has a moderate socioeconomic impact in the Great Lakes.

Realized:

In the Great Lakes, S. palustris hosts larval flatworm parasites that cause cercarial dermatitis in humans (swimmer’s itch) that can reduce the attractiveness of recreational water bodies (Gordy et al. 2018).

Potential:

Notably, lymnaeid snails are known to transmit the trematode, Fasciola hepatica, which can cause the disease fascioliasis in mammals, including humans (Martin 1999). Fascioliasis can severely reduce the productive capacity of some mammals, particularly livestock (e.g., meat and milk) (Hurtrez-Bousses et al. 2001).

There is little or no evidence to support that Stagnicola palustris has significant beneficial impacts in the Great Lakes.

Management:

Regulations (pertaining to the Great Lakes region) There are no regulations for Stagnicola palustris in the Great Lakes region.

Note: Check federal, state/provincial, and local regulations for the most up-to-date information.

Control

Biological

No biological controls are listed for Stagnicola palustris.

Physical

No physical controls are listed for Stagnicola palustris.

Chemical

No chemical controls are listed for Stagnicola palustris.

Note: Check state/provincial and local regulations for the most up-to-date information regarding permits for control methods. Follow all label instructions.

Remarks:

Lymnaidae was originally composed of only one genus, Lymnaea, until 1970. After which, the family was further defined into two genera, Lymnaea and Stagnicola (Clifford 1991; Vinarski 2013). Hubendick (1951) grouped 24 snail populations (which included species of both North American and Eurasian origin) identified by Frank Collins Baker in 1911 under the single nominem “palustris”. Numerous morphological and genetic studies (e.g., Remigio and Blair 1997; Pienkowska et al. 2015) in the past 60 years have further defined the “palustris” populations as actually containing five cryptic species Burch (1988) referred to as “Stagnicola spp."). Stagnicola elodes is one of the five species and is distinct from any of the Eurasian forms, including Stagnicola palustris.

References

(click for full reference list)

Author:

A. Bartos

Contributing Agencies:

Revision Date:

3/18/2023

Citation for this information:

A. Bartos, 2024, Stagnicola palustris (O. F. Müller, 1774): U.S. Geological Survey, Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville, FL, and NOAA Great Lakes Aquatic Nonindigenous Species Information System, Ann Arbor, MI, https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/greatLakes/FactSheet.aspx?Species_ID=3604&Potential=N&Type=0&HUCNumber=DGreatLakes, Revision Date: 3/18/2023, Access Date: 5/2/2024

This information is preliminary or provisional and is subject to revision. It is being provided to meet the need for timely best science. The information has not received final approval by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and is provided on the condition that neither the USGS nor the U.S. Government shall be held liable for any damages resulting from the authorized or unauthorized use of the information.