Branchiura sowerbyi

Common Name:

A tubificid worm

Synonyms and Other Names:

Gilled tubificid worm

Identification:

Branchiura sowerbyi is easily differentiated from other tubificids by the presence of gills (Gustafson 1996). It has a dorsal and a ventral gill pair on each segment in the posterior 25% of the body (Barnes 1980). The worm lives with its head buried in the mud and its tail waving actively in the water above. Branchiura sowerbyi is a large, deep red worm, usually 10–15 cm long as an adult (Wang and Matisoff 1997). Dorsal and ventral setae are different with ventral setae bifurcate and the dorsal setae bifurcate or mixture of two or three types. The anterior dorsal bundles contain 6–9 short setae, and 1–3 capillary setae. The ventral bundles contain 7–11 setae. The tips of the anterior ventral bundles are single and they gradually change into bifid setae behind the fifth segment. The clitellym occupies segments 10, 11, 12. Coelomocytes are sparse or absent (Goodnight 1959, Pennak 1978). Branchiura is prone to fragmenting and anterior fragments may be mistaken for Aulodrilus pluriseta (Gustafson 1996).

Size:

20 to 185 mm long

Native Range:

Branchiura sowerbyi is generally thought to be a native of tropical and subtropical Asia (Mills et al. 1993), but some think it is just most conspicuous in these places and is naturally widespread (Gustafson 1996).

|

|

|

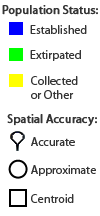

This map only depicts Great Lakes introductions.

|

|

Great Lakes Nonindigenous Occurrences:

This species occurs in California starting in the 1950s. It was first reported in Ohio in 1930. In the Great Lakes system, 1st reported in the Lake Michigan drainage in 1951. Branchiura sowerbyi has also been reported in Lakes Erie, St. Clair, and Huron and the St. Clair and Detroit Rivers (Mills et al. 1993, Spencer and Hudson 2003).

Table 1. Great Lakes region nonindigenous occurrences, the earliest and latest observations in each state/province, and the tally and names of HUCs with observations†. Names and dates are hyperlinked to their relevant specimen records. The list of references for all nonindigenous occurrences of Branchiura sowerbyi are found here.

Table last updated 2/23/2026

† Populations may not be currently present.

Ecology:

Habitat Branchiura sowerbyi is a freshwater benthic deposit feeder that prefers rivers and warmer waters. This species prefers muddy substrate but has been recorded in a variety, including silt-sand, organic matter, and coarse detritus (Liyanage et al. 2003; Perova 2022). B. sowerbyi is adaptable and demonstrates a broad tolerance to water temperature, oxygen concentration, water body type, and water level fluctuation in introduced ranges (Brainard 2018; Yan et al. 2021; Georgieva et al. 2022). See the table below for environmental tolerances reported by Fofonoff et al. (2020):

| | Minimum | Maximum |

| Temperature (ºC) | 4 | 35 |

| Salinity (‰) | 0 | 10.2 |

| Oxygen | Hypoxic | |

| pH | 7.2 | 8.5 |

Food Web

Branchiura sowerbyi is a benthic detrivore that feeds upon organic matter in the sediment along lake or river bottoms (USACE 2024). This species burrows into the sediment to feed (up to 20 cm depth), mixing the sediment and leading to bioturbation (Brainard 2018; Mychek-Londer 2018). B. sowerbyi feeding mobilizes solutes in the sediment, introduces buried organic material to the water column, and its recycling rates are reportedly higher than any other freshwater oligochaete (Wang and Matisoff 1997; Matisoff et al. 1999). Oligochaetes are a prey item for benthivorous fish and predatory invertebrates: likely predators of B. sowerbyi in the Great Lakes includes both native (i.e. whitefish Coregonus clupeaformis) and non-native species (i.e. common carp Cyprinus carpio) (Fofonoff et al. 2020).

Life History

Branchiura sowerbyi has a life expectancy of 1 to 2 years, depending on habitat conditions (Carroll and Dorris 1972). Similar to other oligochaetes, B. sowerbyi is a hermaphrodite that reproduces sexually or asexually through fragmentation, asexual reproduction is the most common (Highnam 1977; USACE 2024). Individuals can reach sexual maturity within 4 months and breeding is reportedly restricted to the warmer months but two reproductive cycles have been observed in optimal conditions (Lobo and Alves 2011). Temperatures between 10-32.5 ºC are required for reproduction (Fofonoff et al. 2020). B. sowerbyi’s tolerance to environmental conditions and broad distribution suggest it is able to adapt its life cycle to local conditions (Carroll and Dorris 1972).

Great Lakes Means of Introduction:

Branchiura sowerbyi was probably introduced to the United States, as well as globally, with the importation of aquarium specimens. It was first discovered in Ohio in 1930 and since then has been widely distributed throughout North America (Mills et al. 1993). Speculation has been that Branchiura sowerbyi was introduced in the Great Lakes by an accidental release from imported aquatic plants in 1951, and subsequently it has appeared in Lake St. Clair and western Lake Erie (Mills et al.1993; Spencer and Hudson 2003). Alternatively, B. sowerbyi may have been naturally widespread, only more conspicuous in warmer waters (Gustafson 1996).

Great Lakes Status:

Reproducing and overwintering in the Great Lakes basin. Widespread with populations in Lake Erie, Lake Huron, Lake Michigan, and Lake St. Clair. Broad distribution throughout the United States.

Great Lakes Impacts:

Summary of species impacts derived from literature review. Click on an icon to find out more...

| Environmental | Socioeconomic | Beneficial |

|

|

| | | |

Current research on the environmental impact of Branchiura sowerbyi in the Great Lakes is inadequate to support proper assessment. Branchiura sowerbyi is a conveyor-belt feeder that mixes benthic sediments, bringing deeper sediments to the surface (Matisoff et al. 1999; Brainard 2018). Because it is larger than other freshwater oligochaetes, B. sowerbyi can burrow deeper into sediment (up to 20 cm), homogenize layers at a greater depth, and transport large amounts of benthic materials to the sediment-water interface (Matisoff et al. 1999; Mychek-Londer 2018).

Branchiura sowerbyi, with other oligochaetes, has been documented as a host of myxosporean parasites which cause fish pathogens such as swim-bladder disease and haemorrhagic thelohanellosis in Asia and Europe, and its presence has been correlated to high levels of infection in fish (Liyanage et al. 2003). B. sowerbyi is an intermediate host for Thelohanellus kitauei, a parasite that causes intestinal giant cystic disease in common carp Cyprinus carpio (Zhao et al. 2016). Several novel parasites have been reported infecting B. sowerbyi in China (Liu et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2022a; Liu et al. 2022b; Liu et al. 2023).

There is little or no evidence to support that Branchiura sowerbyi has significant socio-economic impacts in the Great Lakes.

Branchiura sowerbyi has the potential to negatively impact fish farms due to its role as an intermediate host for the parasite Myxobolus lentisuturalis. This parasite has been observed infecting goldfish at a commercial farm in North Carolina (Hepps Keeney et al. 2023).

Branchiura sowerbyi has a moderate beneficial impact in the Great Lakes.

Branchiura sowerbyi, due to its high productivity and ease of cultivation, has potential to be utilized as a food source for fish farming (Lobo and Alves 2011). Specimens are easy to handle and can be used in ecotoxicological studies (Ghosh and Konar 1983; Marchese and Brinkhurst 1996; Das and Das 2005; Saha et al. 2006; Lobo and Espíndola 2016). B. sowerbyi burrowing and subsequent bioturbation reduces methane (CH4) emission to the atmosphere by increasing methanotrophic activities in the soil (Mitra and Kaneko 2017).

Management:

Regulations

There are no known regulations for this species.

Note: Check federal, state/provincial, and local regulations for the most up-to-date information.

Control

Branchiura sowerbyi has not received much attention regarding control studies. The effects of industrial toxicants on Tubificidae species and explorations of their value as an indicator of environmental quality have been explored, but chemicals and heavy metals are not viable methods of control because of unknown and adverse effects on the surrounding environment (Das and Das 2005, Saha et al. 2006; Saha et al. 2020; Sarkar et al. 2022). However, there has been investigation into the control of Branchiura sowerbyi as a host of haemorrhagic thelohanellosis, which negatively impacts fish in aquaculture (Liyanage et al. 2003).

Biological

Brown trout, Salmo trutta L., has been shown to prey on oligochaetes; its removal from an experimental environment led to rapid multiplication of benthic fauna (Wahab et al. 1989). However, brown trout is itself an invasive species in the Great Lakes region and across nearly all of the United States (Fuller et al. 2013).

Physical

Researchers found that Branchiura sowerbyi, which is a vector in transmission of Thelohanellus hovorkai (myxozoa) to fish, prefers muddy substrate, while other benthic oligochaetes that are not susceptible to myxozoa prefer sandy substrate, and suggested that replacing bottom substrate from mud to sand would lead to a shift in oligochaete communities from Branchiura sowerbyi to non-susceptible oligochaetes such as Limnodrilus socialus, therefore reducing disease in aquaculture fauna (Liyanage et al. 2003).

Chemical

While there are no known chemical controls specifically for Branchiura sowerbyi, declines in Oligochaeta in southern Lake Michigan were recorded between 1980 and 1993 in correlation with reductions in phosphorus loads (Nalepa et al. 1998), suggesting that reduction of excess nutrients would help to reduce oligochaete populations.

Note: Check state/provincial and local regulations for the most up-to-date information regarding permits for control methods. Follow all label instructions.

References

(click for full reference list)

Author:

Liebig, J., J. Larson, A. Fusaro, and C. Shelly

Contributing Agencies:

Revision Date:

7/14/2025

Citation for this information:

Liebig, J., J. Larson, A. Fusaro, and C. Shelly, 2026, Branchiura sowerbyi: U.S. Geological Survey, Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville, FL, and NOAA Great Lakes Aquatic Nonindigenous Species Information System, Ann Arbor, MI, https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/greatlakes/FactSheet.aspx?Species_ID=1151, Revision Date: 7/14/2025, Access Date: 2/23/2026

This information is preliminary or provisional and is subject to revision. It is being provided to meet the need for timely best science. The information has not received final approval by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and is provided on the condition that neither the USGS nor the U.S. Government shall be held liable for any damages resulting from the authorized or unauthorized use of the information.