Cirsium palustre

(L.) Scop.

Common Name:

Marsh thistle

Synonyms and Other Names:

Marsh plume thistle, European marsh thistle, European swamp thistle, Eurasian marsh thistle, cirse ou chardon des marais, Carduus palustris Linnaeus, Cnicus palustris (L.) Willd.

Identification:

Biennials or monocarpic perennials, 30–200 cm; clusters of fibrous roots.

Stems: single, erect, villous to tomentose with jointed trichomes, distally tomentose with fine, unbranched trichomes; branches 0–few, ascending, (short). Thick, with spiny lengthwise wings along stem; sometimes reddish; branching at the top.

Leaves: blades narrowly elliptic to oblanceolate, 15–30+cm by 3–10 cm, margins shallowly to very deeply pinnatifid, narrow lobes separated by broad sinuses, spiny-dentate to lobed, main spines 2–6 mm, abaxial villous to tomentose with jointed trichomes, sometimes also thinly tomentose with fine unbranched trichomes, adaxial faces villous with septate trichomes or glabrate; basal often present at flowering, petioles spiny-winged, bases tapered; cauline many, sessile, gradually reduced and becoming widely spaced above, bases long-decurrent with prominently spiny wings; distal cauline deeply pinnatifid with few-toothed spine-tipped lobes. Thin, deeply lobed into pinnate segments, covered with loose matted hairs and spiny teeth along margins, up to 20 cm (8 in) long; basal leaves longer than those higher in the stem in flowering plants; leaves of basal rosettes (first year plants) are spiny, deeply lobed, long and hairy below.

Flowers: Spiny, purple flowerheads composed of disc flowers. Heads few–many in dense clusters at branch tips. Peduncles 0–1 cm. Involucres ovoid to campanulate, 1–1.5 by 0.8–1.3 cm, thinly cobwebby tomentose with fine unbranched trichomes. Phyllaries in 5–7 series, strongly imbricate. greenish, or with purplish tinge, lanceolate to ovate (outer) or linear-lanceolate (inner), margins thinly arachnoid-ciliate, abaxial faces with narrow glutinous ridge, outer and middle appressed, entire, apices acute, mucronate or spines erect or spreading, weak, 0.3–1 mm; apices of inner phyllaries purplish, linear-attenuate, scarious, flat. Corollas lavender to purple (white), 11–13 mm, tubes 5–7 mm, throats 2–3 mm, lobes 3–4.5 mm; style tips 1.5–2 mm.

Fruits/Seeds: Fruit is a tiny achene, 3 mm long; attached to a pappus or thistledown. Cypselae tan to stramineous, 2.5–3.5 mm, apical collars 0.1–0.2 mm, shiny; pappi 9–11 mm. 2n = 34. Stems:

Size:

0.5-2 m (1.5-6.5 ft) tall.

Native Range:

Eurasia

|

|

|

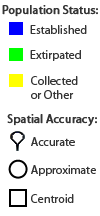

This map only depicts Great Lakes introductions.

|

|

Great Lakes Nonindigenous Occurrences:

This introduction and subsequent invasion has established it on both sides of the Atlantic ocean in the northern latitudes. It was first recognized earlier this century in North America and collected in Newfoundland and New Hampshire. The earliest record in New England seems to be from East Andover, New Hampshire in 1902. The botanist who located this population of the plant in a "moist forest tangle" some 20 acres in size, couldn't figure out how it had gotten there, as it was more than a mile from any town or cultivation. Other early records come from South Boston (1908) and Newfoundland (1910). Though it is not clear how it arrived, it has slowly spread west and, to a lesser degree, south.

In Michigan, C. palustre is an introduced species that was transported from Western Europe in the early twentieth century, and has since established itself as an aggressive weed. It has spread voraciously from Michigan's Upper Peninsula, where it was first collected in Marquette County in 1934, to the Lower Peninsula where it was assimilated by 1959. 1st Great Lakes report in1950 in Lake Superior. Also reported in St. Pierre and Miquelon; B.C., Nfld. and Labr., N.S., Ont., Que.; Mass., Mich., N.H., N.Y., Wis.

Table 1. Great Lakes region nonindigenous occurrences, the earliest and latest observations in each state/province, and the tally and names of HUCs with observations†. Names and dates are hyperlinked to their relevant specimen records. The list of references for all nonindigenous occurrences of Cirsium palustre are found here.

Table last updated 2/22/2026

† Populations may not be currently present.

Ecology:

Cirsium palustre has been classified as both a biennial and a monocarpic perennial (Pons and During 1987). Flowering and reproduction typically occur within two years, but C. palustre may remain in a vegetative state for a longer period of time if environmental conditions are unfavorable or if the density of C. palustre or other vegetation is high (Fraser 2000). The rosette must reach a sufficient size (generally at least 20 cm in diameter) in order for flowering to occur. It typically flowers June through August, is capable of self-pollination, and can produce up to 2,000 seeds per plant (Fraser 2000, Sheehan 2007). Like other thistles, its seeds are readily dispersed by wind and water, as well as through ingestion and deposit by birds and animals (Campbell et al. 2010, Fraser 2000). Under stormy or high convective conditions, terminal seed velocity can reach 0.3 m/s and seeds can travel upwards of several kilometers (Soons 2006). Preferred conditions for C. palustre germination are a period of moist cold (i.e. cold stratification), followed by full sunlight and warm temperatures (optimal temperature ≥ 12°C (54°F)) (Gucker 2009). Germination may occur from April to November, but emergence is most common in late spring and fall. Vegetative cover, shading, and inadequate water conditions may inhibit germination (Fraser 2000).

There are discrepancies in current literature about seed bank longevity (Gucker 2009). In a series of experiments, Pons (1984) determined that high temperatures and reduced access to light induced dormancy in seeds. Pons (1984) also concluded that light is the principle stimulus for germination.

Cirsium palustre prefers moist, acidic soils and is found along roadsides and in wide variety of wetlands, wet forests and forest edges, marshes, and fields. In Michigan, it also colonizes cedar swamps, which are exposed by frequent breaks in cover (Voss 1996).

Populations appear to vary in size and density. Vegetative rosettes often outnumber flowering plants and can densely carpet some areas (Fraser 2000). In Europe, C. palustre behaves as an early successional species, and populations are described as short-lived—declining as rosettes begin to be shaded out by other herbaceous and woody plants (Fraser 2000). Such successional dynamics do not appear to be consistent in invasive populations, where shade does not always limit individual growth and population size (Nordin 2002).

Means of Introduction:

Unknown

Status:

Noxious weed

Great Lakes Impacts:

Summary of species impacts derived from literature review. Click on an icon to find out more...

| Environmental | Socioeconomic | Beneficial |

|

|

| | | |

Cirsium palustre has a moderate environmental impact in the Great Lakes.

Realized:

Realized impacts on native species and habitats following establishment have yet to be comprehensively documented or investigated (NatureServe 2010). However, concern exists over the rapidly expanding range of C. palustre in the Great Lakes region (e.g., its southward movement in Michigan; Voss 1996). Cirsium palustre can spread aggressively, resulting in reduced biodiversity and compromised ecological integrity, especially in the wetland ecosystems of Great Lakes islands (Cuthbert et al. 2007, USDA Forest Service 2005b). Its migration is vigorous along roadsides, where it appears to be facilitated by human transportation, including, where applicable, the logging industry (Reznicek et al. 2011).

Potential:

This plant is capable of spreading into open, undisturbed wetlands and forming clumps or impenetrable stands of flowering stalks or carpets of rosettes, potentially displacing native vegetation, altering community structure, and threatening natural diversity (Fraser 2000). Marsh thistle is able to produce 2,000 viable seeds per plants; therefore, only a few plants are needed to have a drastic impact on the seed bank of an area (Fraser 2000, Sheehan 2007). Cirsium palustre poses a threat to C. pitcheri (Torr. ex Eaton) Torr. & A. Gray, which is native to the Great Lakes region and is classified as threatened by the U.S. federal government and the province of Ontario (COSSARO 2011, USDA NRCS 2012a). Native swamp thistle, C. muticum, may also be at risk for adverse competitive effects (GLIFWC 2006). There is some evidence that C. palustre may be allelopathic, although this possibility has not been thoroughly investigated (Ballegaard and Warncke 1985).

In Europe, Cirsium arvense (a native to the Great Lakes) invades native populations of C. palustre and hybridization between the two species has occurred. Such hybridization is possible in North America where these species grow in close proximity, but none has been reported in the Great Lakes (Gucker 2009). Marsh thistle is managed as a high priority species in the Chequamegon Nicolet National Forest (WI), where it is considered a threat to some high quality native areas, but it is not a major concern in all areas (USDA Forest Service 2005a). In British Colombia, C. palustre has been blamed for the degradation of sedge (Carex spp.) meadows (Sheehan 2007). This species could pose a threat to native sedge communities–especially to rare, threatened, or endangered species (USDA NRCS 2012b).

There is little or no evidence to support that Cirsium palustre has significant socio-economic impacts in the Great Lakes.

Potential:

Although it is reportedly not a threat to cultivated agricultural areas, C. palustre may reduce forage quality in damp pastures following establishment. It could form dense clumps in logged cut blocks, competing for moisture and nutrients with tree seedlings planted for reforestation. Tall stems can lead to snow press, permanently damaging tree seedlings (OLA and MAFF 2002).

There is little or no evidence to support that Cirsium palustre has significant beneficial effects in the Great Lakes.

Potential:

Polyphenolic compounds extracted from Cirsium palustre exhibit anti-microbial properties (Nazaruk et al. 2008).

Management:

Regulations (pertaining to the Great Lakes region)

Cirsium palustre is considered to be a medium to high threat species in New York and Michigan (Higman and Campbell 2009, New York Invasive Species Council 2010). Cirsium palustre became a prohibited species in some Wisconsin counties with the creation of Wisconsin's Invasive Species Identification, Classification and Control Rule (Chapter NR40)(Terrestrial Herbaceous Plants Species Assessment Group 2007). Even though it is not present in Minnesota, it is characterized as a severe threat to native ecosystems based on its impact in other locations (Minnesota Invasive Species Advisory Council 2009). Marsh thistle is listed as an introduced species in Ontario and Quebec (Canadensys 2012). It is considered noxious in some regions of British Columbia under the Weed Control Act (OLA and MAFF 2002). Marsh thistle was categorized as a priority species for removal by the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC) in 2006, but this priority was reduced in subsequent comprehensive reports (Falck et al. 2006, 2009a, b) Note: Check federal, state/provincial, and local regulations for the most up-to-date information.

Control

Biological

While there are no specific biocontrol agents for C. palustre (GLIFWC 2006), herbivory by a variety of species may be beneficial but requires additional research.

Promising biocontrol candidates include a European seedhead fly, Terellia ruficauda (Fraser 2000, OLA and MAFF 2002); the seed-eating weevil, Rhinocyllus conicus, currently undergoing experimental trial in the Robson Valley Forest District, British Columbia (OLA and MAFF 2002, USDA Forest Service 2005); and the glassy cutworm, Apamea devastator (native in New York and Ohio; Volger and Stressler 2011). The latter is an indiscriminate herbivore known to feed on C. palustre and may help control marsh thistle; however, this moth feeds on a broad spectrum of additional plants.

Larvae of the artichoke plume moth (Platyptilia carduidactyla) also feed on marsh thistle, but as its common name suggests, this species is considered a pest to artichokes. Furthermore, the moth’s native range is south of the Great Lakes (Winston et al. 2008). Occasionally Cheilosia corydon, a fly native to Italy, feeds on marsh thistle (Winston et al. 2008). This fly was released in Oregon in 1991 to control several invasive thistle populations. However, since its release, C. corydon populations have attacked native and exotic thistles indiscriminately (ODA, Plant Division 2011). Additional insects that feed on and/or use C. palustre for part of their life cycle are listed on the websites of J. Lindsey (http://www.commanster.eu/commanster/Plants/Flowers/SpFlowers/Cirsium.palustre.html) and the Encyclopedia of Life (http://eol.org/data_objects/8731293).

Goats are attracted to the flowering stage of many thistles, including C. palustre. Only about 0.5% of thistle seeds that pass through their digestive systems remain viable, making it unlikely that they would aid in the spread of this species. Effective grazing could reduce marsh thistle populations, although it is unclear whether grazing would ultimately control C. palustre via the trampling of rosettes or facilitate its spread through the creation of safe sites for germination (Fraser 2000). Reseeding of native vegetation may enhance the success of prior control efforts. Moreover, goats do not select for marsh thistle and may also eat native thistles in intermingled communities (Popay and Field 1996).

Van Leeuwen found that a combination of European grazers (rabbits, the hoverfly Cheilosia grossa, and Epiblema scutula) resulted in an approximately 30% reduction in flower heads on Cirsium palustre. Furthermore, plants that had suffered predation had a reduced stem height, resulting in a reduced seed dispersal distance of surviving achenes (van Leeuwen 1983). Additional research is needed to determine if native species of rabbits and insects could have similar results on controlling C. palustre in the Great Lakes.

Physical

All physical control efforts need to be carefully executed and monitored for several years before reducing C. palustre infestations (GLIFWC 2006, Sheehan 2007).

Where infestations are small, hand pulling may be effective. In Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest (CNNF), Wisconsin, individual plants were mechanically controlled by cutting the root just below the surface with a spade (GLIFWC 2006, USDA Forest Service 2005a). This method is most effective if completed before flowering so that all plant material can be left on site to decompose (Invasive Plant Council of British Columbia 2008). If this method is implemented while flowers and seeds are present, flower heads must be bagged and removed from site; the remaining plant material can be left on site (Invasive Plant Council of British Columbia 2008).

Mowing before plants flower may reduce the release of seeds (OLA and MAFF 2002); however, there is a risk of regrowth with extra flower heads, and extensive mowing of rosettes could promote growth of this early successional species once mowing ceases (Fraser 2000, Nordin 2002). Repeated close mowing can reduce a C. palustre infestation in three to four years (Gumbart 2012.). Mowing a minimum of three times per growing season can be enough to weaken the following year’s population (Boos et al. 2010). However, in a study by Falinska (1999), the density of C. palustre seeds in the soil decreased dramatically as time since last mowing increased, indicating that frequent mowing may actually increase the density of marsh thistle in the seedbank.

Little is known about marsh thistle response to fire as a control strategy (Gucker 2009).

Chemical

Foliar spray with clopyralid or metsulfuron-methyl is the preferred chemical treatment for C. palustre in CNNF, Wisconsin (USDA Forest Service 2005). However, glyphosate must be used in areas that are wet or near open water (USDA Forest Service 2005). Either of these two treatments are most effective if applied in the spring when plants are 6 to 10 inches tall and still in the budding stage or applied directly to the flower heads in the fall (Boos et al. 2010, USDA Forest Service 2005b). To minimize damaging other non-target species when using glyphosate, stems should be cut close to the ground and a small amount sprayed onto the cut area (Sheehan 2007).

Note: Check state/provincial and local regulations for the most up-to-date information regarding permits for control methods. Follow all label instructions.

Remarks:

Similar species: The native Marsh Thistle (Cirsium muticum) has non-spiny stems and flower heads. Other common invasive thistles include Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense) which has spiny leaves but non-spiny stems and flower heads. Bull thistle (Cirsium vulgare) and Plumeless thistle (Carduus acanthoides) which have sharply spined leaves, stems and flower heads.

Spontaneous hybrids between C. palustre and C. arvense have been reported from England and other European countries (W. A. Sledge 1975) and can be expected wherever these species grow together in North America.

References

(click for full reference list)

Author:

Cao, L., J. Larson, L. Berent, and A. Fusaro

Contributing Agencies:

Revision Date:

11/16/2018

Citation for this information:

Cao, L., J. Larson, L. Berent, and A. Fusaro, 2026, Cirsium palustre (L.) Scop.: U.S. Geological Survey, Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville, FL, and NOAA Great Lakes Aquatic Nonindigenous Species Information System, Ann Arbor, MI, https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/greatlakes/FactSheet.aspx?Species_ID=2702, Revision Date: 11/16/2018, Access Date: 2/22/2026

This information is preliminary or provisional and is subject to revision. It is being provided to meet the need for timely best science. The information has not received final approval by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and is provided on the condition that neither the USGS nor the U.S. Government shall be held liable for any damages resulting from the authorized or unauthorized use of the information.