Stephanodiscus binderanus

Krieger, 1927

Common Name:

A centric diatom

Synonyms and Other Names:

Melosira binderana Kutzing, 1844

Identification:

This diatom is an obligate colonial species that occurs in filaments. Valve faces are flat but may exhibit some concentric undulation and occur at right angles to valve mantles. Valve spines are forked. On occasion some cells exhibit occluded or slit-shaped areolae. Thick pores occur in a ring on the mantle. Vacuoles comprise around 40% of cell volume (Round 1972, 1982, Stoermer and Sicko-Goad 1985). In Saginaw Bay, Lake Huron, the cell volume of S. binderanus is around 830 µm3 (Sicko-Goad et al. 1977).

Size:

Volume is approximately 830 cubic microns

Native Range:

Stephanodiscus binderanus was first described from the Baltic Sea and is considered a Eurasian species (Mills et al. 1993). However, it has expanded its range within Eurasia to places where it was not previously recorded. (Also see Remarks.)

|

|

|

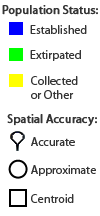

This map only depicts Great Lakes introductions.

|

|

Great Lakes Nonindigenous Occurrences:

Stephanodiscus binderanus was first recorded from Lake Michigan in 1938. However, sediment samples indicate that it could have occurred by 1930 in Lake Erie and by around the late 1940s to early 1950s in Lake Ontario. It also now occurs in Lake Huron and the Cuyahoga River, which is part of the Lake Erie drainage (Mills et al. 1993, Stoermer et al. 1996, Stoermer and Yang 1970, Williams 1972).

Stephanodiscus binderanus populations in Lake Erie and Lake Michigan have fluctuated over time. From the 1930s to 1960s, both lakes experienced eutrophication and, as a result, S. binderanus increased in abundance. By the end of that period, the density of S. binderanus in Lake Michigan ranged from 98 cells/mL to 1617 cells/mL, accounting for 14.6% of lake biomass. Spring blooms were associated with the excursion of the spring thermal bar and were limited to eutrophic nearshore areas in Lake Michigan, but occurred in both nearshore and offshore waters in Lake Erie and Lake Ontario (Danforth and Ginsbur 1980, Makarewicz 1981, Stoermer and Ladewski 1976). As anthropogenic inputs to the lakes began to be addressed in the 1970s and 1980s, these systems returned to more oligotrophic-mesotrophic conditions, and S. binderanus concentrations plummeted. In the 1980s, the maximum density S. binderanus in Lake Erie was 1,549 cells/mL, accounting for only 0.56% of the total cells collected. However, in the early 1990s, S. binderanus increased again in abundance in Lake Erie, only to drop to low levels by the end of that decade (Barbiero et al. 2006, Danforth and Ginsburg 1980, Makarewicz 1993, Makarewicz and Baybutt 1981, Stoermer et al. 1975, Stoermer et al. 1996, Tarapchak and Stoermer 1976).

Table 1. Great Lakes region nonindigenous occurrences, the earliest and latest observations in each state/province, and the tally and names of HUCs with observations†. Names and dates are hyperlinked to their relevant specimen records. The list of references for all nonindigenous occurrences of Stephanodiscus binderanus are found here.

Table last updated 4/23/2024

† Populations may not be currently present.

Ecology:

Stephanodiscus binderanus often reaches high abundance in eutrophic and/or slightly brackish conditions. It is very tolerant of osmotic variability. Blooms are typically recorded in spring and fall in many water bodies, although there are also some records in summer. In the Great Lakes, it usually occurs in eutrophic areas in the thermal bar region. It is most abundant in colder seasons but may persist in relatively polluted areas throughout summer. Resting cells are typically triggered to reinitiate growth by changes in temperature, nutrients, and other abiotic conditions (Kling 1998, Laugasta et al. 1996, Mills et al. 1993, Round 1972, Sicko-Goad et al. 1989, Sommer 1984, Stoermer et al. 1975, Stoermer and Ladewski 1976, Stoermer and Yang 1970, Tarapchak and Stoermer 1976). In Lake Michigan, blooms of S. binderanus have been recorded both in spring and fall. Highest abundance in nearshore areas typically occurs at water temperatures around 8–9°C (Lauer 1976, Round 1972, Stoermer and Ladewski 1976). In Lake Erie, peaks in abundance have been recorded in spring, which is the largest peak, and also around November/December. In Lake Ontario, abundance typically reaches a maximum after the thermal bar spring excursion and declines sharply in summer. In Lakes Erie and Ontario, blooms typically occur in offshore and often central regions (Barbiero and Tuchman 2001, Round 1972, Stoermer and Ladewski 1976). In the Cuyahoga River, S. binderanus has been known to occur at temperatures of 26°C (Williams 1972). It has also been recorded in the north channel of the St. Lawrence estuary at biovolumes over 50% in salinities of 1–5.5 psu (Winkler et al. 2003).

Stephanodiscus binderanus also sometimes occurs at river outlets into lakes. It requires silicon for growth, but populations can persist in low silicon conditions until this resource increases in abundance. Filaments are frequently grazed efficiently by zooplankton in native regions. This species grows best in 12 hours of light and 12 hours of dark (Holopainen and Letanskaya 1999, Knisely and Geller 1986, Sicko-Goad and Andersen 1991, Sommer and Stabel 1983).

In the former USSR, S. binderanus tends to be a eurythermal species that blooms around 15–16°C in the spring and 19–20°C in the summer, and typically occurs in large lakes and reservoirs. It was historically limited to northern regions of the USSR and only a few more southerly locations, but this changed with the building of more reservoirs in southern regions. It is likely that this species requires sediments to overwinter, which often accumulate well in larger lakes and reservoirs (Priymachenko 1973). In Lake Baikal, where it is not endemic, its presence is associated with increasing anthropogenic impacts (Edlund et al. 1995).

Means of Introduction:

Stephanodiscus binderanus was very likely introduced to the Great Lakes basin in ships’ ballast water (Mills et al. 1993).

Status:

Established where recorded.

Great Lakes Impacts:

Summary of species impacts derived from literature review. Click on an icon to find out more...

| Environmental | Socioeconomic | Beneficial |

|

|

| | | |

Stephanodiscus binderanus has a moderate environmental impact in the Great Lakes.

Realized:

The introduction and establishment of S. binderanus, along with Actinocyclus normanii f. subsalsa, were accompanied by the reduction of five native diatoms (S. transilvanicus, Cyclotella comta, C. michiganiana, C. ocellanta, and C. stelligera) in Lake Ontario (Edlund et al. 2000, Stoemer et al. 1985). While it is unclear if these local population reductions were due entirely or in part to competition with exotic taxa, the appearance of S. binderanus in Lake Ontario spring diatom collections tends to be associated with the absence or rare occurrence of C. comta, C. michiganiana, C. ocellanta, and C. stelligera (US EPA 2012). These native species reappear at sample sites in summer, when S. binderanus is not longer found (US EPA 2012), suggesting that strong seasonal competition may drive fluctuations in native diatom abundances.

Stephanodiscus bineranus thrives in phosphorous rich and silica depleted waters. It reached peak abundance in Lake Michigan and Lake Ontario in the 1950s and 1960s, but since efforts to improve water quality began in the 1970s and grazing from the Dreissena invasion increased in the 1980s, there have been marked declines in S. binderanus populations (Barbiero et al. 2006, Stoermer et al. 1996). In a more recent survey conducted in 2001, S. binderanus was not found Lakes Superior, Michigan, or Huron. However, S. binderanus was present in Lake Ontario and had a few very large populations in Lake Erie reaching biovolumes of 32,028 ug/mL (Barbiero and Tuchman 2001). Current environmental impacts of this species are unknown.

Stephanodiscus binderanus has a moderate socio-economic impact in the Great Lakes.

Realized:

Stephanodiscus binderanus has clogged filters at water filtration plants in both Chicago and Montreal, and has caused water taste and odor problems (Brunel 1956, Stoermer and Yang 1970, Stoermer et al. 1996, Vaughn 1961). Stephanodiscus binderanus also forms surface scums and, at high abundances, reduces water quality, and negatively affects recreational uses of the affected lake (Stoermer et al. 1985).

There is little or no evidence to support that Stephanodiscus binderanus has significant beneficial effects in the Great Lakes.

Potential:

Stephanodiscus binderanus has been used to assess historical pollution and climate conditions both in the Great Lakes and in Lake Baikal, Russia (Edlund et al. 1995, Stoermer et al. 1985).

Management:

Regulations (pertaining to the Great Lakes region)

There are no known regulations for this species.

Note: Check federal, state/provincial, and local regulations for the most up-to-date information.

Control

Biological

There are no known biological control methods for this species.

Physical

There are no known physical control methods for this species.

Chemical

Stephanodiscus binderanus thrives in eutrophic waters. The reduction of pollution and nutrient run-off could decrease the viable habitat for S. binderanus.

Note: Check state/provincial and local regulations for the most up-to-date information regarding permits for control methods. Follow all label instructions.

Remarks:

Stephanodiscus binderanus was first recorded in the St. Lawrence River near Montreal in 1955 (Mills et al. 1993). Stephanodiscus binderanus is synonymous with Melosira binderana. Alternate spellings sometimes found in the literature are S. binderianus and M. binderiana. A recent study conducted by Hawrshyn et al. (2012) in Lake Simcoe, Ontario found historical microfossils of S. binderanus dating back the 17th century. This discovery brings the status of S. binderanus as a nonindigenous species in the Great Lakes basin into question. Stephanodiscus binderanus may be better classified as a range expander rather than as a nonidigenous species.

References

(click for full reference list)

Author:

Kipp, R.M., M. McCarthy, and A. Fusaro

Contributing Agencies:

Revision Date:

9/12/2019

Citation for this information:

Kipp, R.M., M. McCarthy, and A. Fusaro, 2024, Stephanodiscus binderanus Krieger, 1927: U.S. Geological Survey, Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville, FL, and NOAA Great Lakes Aquatic Nonindigenous Species Information System, Ann Arbor, MI, https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/greatlakes/FactSheet.aspx?Species_ID=1687&Potential=N&Type=0&HUCNumber=DHuron, Revision Date: 9/12/2019, Access Date: 4/23/2024

This information is preliminary or provisional and is subject to revision. It is being provided to meet the need for timely best science. The information has not received final approval by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and is provided on the condition that neither the USGS nor the U.S. Government shall be held liable for any damages resulting from the authorized or unauthorized use of the information.