Channa aurolineata

(Goldline Snakehead)

Fishes

Exotic |

|

Common name: Goldline Snakehead

Synonyms and Other Names: Bullseye Snakehead, giant snakehead, great snakehead, cobra snakehead, Indian snakehead, giant murrel. Courtenay and Williams (2004) provide a larger list, including names used in other languages. Specimens in Florida were formerly identified at Channa marulius (Hamilton, 1822).

Taxonomy: available through

www.itis.gov

Identification: Snakeheads (family Channidae) are morphologically similar to the North American native Bowfin (Amia calva), and identification of the two are often confused. Morphological differences used for identification between the two are depicted here. Snakeheads are distinguished from Bowfin by the position of pelvic fins (directly behind pectoral fins in snakeheads, farther posterior in Bowfin) and the size of the anal fin (elongate and similar in size to dorsal fin in snakeheads, short and much smaller than dorsal fin in Bowfin). Additionally, Bowfin can be identified by the presence of a bony plate between the lower jaws (gular plate) and a distinctive method of swimming using undulations of the dorsal fin. Goldline Snakehead has a distinctive orange spot (ocellus) on caudal peduncle that may fade with growth. One of the largest species of Channa (Talwar and Jhingran 1992).

Size: to ~120 cm TL (Talwar and Jhingran 1992)

Native Range: Myanmar (Salween, Chindwin, Sittang, and Ayeyarwady River basins) and western Thailand (Mae Khlong River basin) (Adamson and Britz 2018, 2019).

|

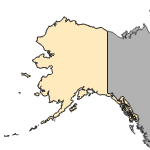

Alaska |

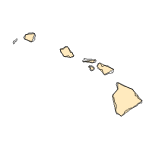

Hawaii |

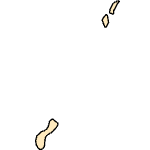

Puerto Rico &

Virgin Islands |

Guam Saipan |

Hydrologic Unit Codes (HUCs) Explained

Interactive maps: Point Distribution Maps

Nonindigenous Occurrences:

This snakehead is found in many residential lakes and canals in Broward and Palm Beach counties, Florida (Shafland et al. 2008).

Table 1. States with nonindigenous occurrences, the earliest and latest observations in each state, and the tally and names of HUCs with observations†. Names and dates are hyperlinked to their relevant specimen records. The list of references for all nonindigenous occurrences of Channa aurolineata are found here.

Table last updated 1/17/2026

† Populations may not be currently present.

Ecology: Prefers deep clear lakes and rivers with rocky or sandy substrate (Talwar and Jhingran 1992), although other authors report them inhabiting standing water in canals, lakes, and swamps with submerged aquatic vegetation (Rainboth 1996). Spawning period and timing seems to vary geographically, but generally occurs between May to August (summarized by Courtenay and Williams 2004). Snakeheads exhibit parental care, with parents guarding eggs/juveniles in a nest until the young reach ~10 cm in length (Courtenay and Williams 2004). Snakeheads have an air-breathing organ and are capable of extracting oxygen from both water and air, with oxygen uptake from air representing a large portion of total oxygen acquired. Adult snakeheads require surface oxygen to meet total respiratory requirements (Ojha et al. 1979). Goldline Snakehead are predatory, with fishes and crustaceans comprising the majority of its diet (summarized as Bullseye Snakehead in Courtenay and Williams 2004).

Means of Introduction: Unknown, but illegally introduced in Florida most likely as a food source for human consumption. Through DNA barcode testing, Thailand was suggested as the likely source of the Florida population (Adamson and Britz 2019).

Status: This snakehead is established and found in many residential lakes and canals in Broward and Palm Beach counties, Florida (Shafland et al. 2008, Benson et al. 2018).

Impact of Introduction: Summary of species impacts derived from literature review. Click on an icon to find out more...

| Ecological | Economic | Human Health | Other |

|

|

|

| | | | |

Unknown. This predatory species has the potential to impact native fishes and crustaceans directly. Bullseye snakeheads have been found to consume native centrarchids, lizards, toads, and small fishes; however, snakeheads are also consumed by other large predatory fishes present in south Florida canals (e.g., Largemouth Bass Micropterus salmoides and Butterfly Peacock bass Cichla ocellaris; P. Shafland, pers. comm.). Bioaccumulation of mercury and arsenic could pose a human health risk if this fish is consumed by humans (Krishna et. al. 2018, Qadir et al. 2006).

References: (click for full references)

Adamson, E.A.S., and R. Britz. 2018. The snakehead fish Channa aurolineata is a valid species (Teleostei: Channidae) distinct from Channa marulius. Zootaxa 4514(4):542-552. https://www.biotaxa.org/Zootaxa/article/view/zootaxa.4514.4.7 Adamson, E.A.S., and R. Britz. 2019. The Mae Khlong Basin as the potential origin of Florida’s feral bullseye snakehead fish (Pisces: Channidae). Raffles Bulletin of Zoology 67:403-411.

Benson, A.J., P.J. Schofield, and K.B. Gestring. 2018. Introduction and dispersal of non-native bullseye snakehead Channa marulius (Hamilton, 1822) in the canal system of southeastern Florida, USA. BioInvasions Records 7(4):451-457.

Courtenay, W.R., Jr., and J.D. Williams. 2004. Snakeheads (Pisces: Channidae): A biological synopsis and risk assessment. Circular 1251, US Geological Survey, Gainesville, FL.

Krishna, P.V., S.K. Saleem Basha, K.G. Sathyavani, and K. Prabhavathi. 2018. Heavy metal bioaccumulation in the Channa marulius from Lake Kolleru and human health risk assessment. International Journal of Zoology Studies 3(1): 76-79.

Ojha, J., N. Mishra, M.P. Saha, and J.S.D. Munshi. 1979. Bimodal oxygen uptake in juveniles and adult amphibious fish, Channa (=Ophiocephalus) marulius. Hydrobiologia 63(2):153-159.

Qadir Shaha, A., T. Gul Kazi, M. Balal Arain, J. Ahmed Baig, H. Imran Afridi, G. Abbas Kandhro, S. Khan, and M. Khan Jamali. 2009. Hazardous impact of arsenic on tissues of same fish species collected from two ecosystem. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 167: 511-515.

Rainboth, W.J. 1996. Fishes of the Cambodian Mekong. FAO Species Identification Field Guide for Fishery Purposes. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome. http://www.fao.org/docrep/010/v8731e/v8731e00.htm

Shafland, P.L., K.B. Gestring, and M.S. Stanford. 2008. Florida's exotic freshwater fishes - 2007. Florida Scientist 71(3):220-245.

Shrestha, T.K., 1990. Resource ecology of the Himalayan waters. Curriculum Development Centre, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Talwar, P.K. and A.G. Jhingran. 1992. Inland fishes of India and adjacent countries, Vol. 2: Balkema Publishers, Rotterdam.

Author:

Fuller, P.L., A.J. Benson, M.E. Neilson, and K.M. Reaver

Revision Date: 7/14/2022

Peer Review Date: 4/21/2015

Citation Information:

Fuller, P.L., A.J. Benson, M.E. Neilson, and K.M. Reaver, 2026, Channa aurolineata (Hamilton, 1822): U.S. Geological Survey, Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville, FL, https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.aspx?SpeciesID=2266, Revision Date: 7/14/2022, Peer Review Date: 4/21/2015, Access Date: 1/18/2026

This information is preliminary or provisional and is subject to revision. It is being provided to meet the need for timely best science. The information has not received final approval by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and is provided on the condition that neither the USGS nor the U.S. Government shall be held liable for any damages resulting from the authorized or unauthorized use of the information.