Gila atraria

(Utah Chub)

Fishes

Native Transplant |

|

Common name: Utah Chub

Taxonomy: available through

www.itis.gov

Identification: Simpson and Wallace (1978); Sigler and Sigler (1987); Page and Burr (1991); Bond (1994).

Size: 56 cm.

Native Range: Upper Snake River system, Wyoming and Idaho, and Lake Bonneville basin (including Great Salt Lake drainage and Sevier River system), southeastern Idaho and Utah (Page and Burr 1991).

|

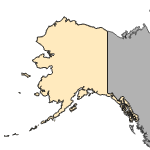

Alaska |

Hawaii |

Puerto Rico &

Virgin Islands |

Guam Saipan |

Hydrologic Unit Codes (HUCs) Explained

Interactive maps: Point Distribution Maps

Nonindigenous Occurrences:

Table 1. States with nonindigenous occurrences, the earliest and latest observations in each state, and the tally and names of HUCs with observations†. Names and dates are hyperlinked to their relevant specimen records. The list of references for all nonindigenous occurrences of Gila atraria are found here.

Table last updated 2/22/2026

† Populations may not be currently present.

Means of Introduction: Many introductions have been the result of bait bucket releases (Holden and Stalnaker 1975b; Simpson and Wallace 1978; Sigler and Sigler 1987). Hubbs et al. (1974) found evidence that the species may have been introduced to certain sites in the Great Basin by early Mormon settlers. These researchers also speculated that Native Americans may have brought Utah Chubs into Shoshone Spring. The species may have been introduced to Murphy Spring, in Steptoe Valley, as forage for sportfish, although its establishment may have resulted from bait bucket releases (Hubbs et al. 1974). In some areas the species has become widespread because of natural dispersal from original points of introduction (e.g., Madison and Missouri rivers in Montana). Holden (1991) stated that it first appeared in Flaming Gorge Reservoir on the Wyoming-Utah border in 1964.

Status: Established in Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, Montana, Utah, Wyoming, and apparently Oregon. It is considered rare or incidental in the Green and Yampa rivers in Colorado, and in the Dolores, Green, and Price rivers in Utah. It is abundant in Flaming Gorge Reservoir in Utah and Wyoming (Tyus et al. 1982).

Impact of Introduction: Introduced populations often reach great abundance and become serious competitors with sport fish, especially trout (Sigler and Miller 1963). For instance, this species has been found to depress growth of kokanee salmon Oncorhynchus nerka through competition for food (Teuscher and Luecke 1996). Hubbs et al. (1974) also noted that it has a tendency toward population explosion and habitat dominance in artificial impoundments. Utah Chub became a major management concern in Flaming Gorge Reservoir by the late 1960s, in part, because it appeared to compete with trout for planktonic foods and because the species established growth records of its own (Holden 1991). Introduced Utah Chub, along with other introduced species, may have replaced the relict dace Relictus solitarius at Murphy Spring, Nevada (Hubbs et al. 1974). Predation by, and hybridization with, the Utah Chub are considered some of the most serious hazards to the least chub Iotichthys phlegethontis in Utah (Sigler and Sigler 1987), a species proposed for federal listing as an endangered species (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1997). Attempts at eradication have been largely unsuccessful and costly (Sigler and Sigler 1987).

References: (click for full references)

Holden, P.B. 1991. Impacts of Green River poisoning on management of native fishes. Pages 43-55

in W.L. Minckley and J.E. Deacon (eds). Battle against extinction: native fish management in the American West. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Hubbs, C.L., R.R. Miller, and L.C. Hubbs. 1974. Hydrographic history and relict fishes of the north-central Great Basin. Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences 7:1-259.

Miller, R.R. 1952. Bait fishes of the lower Colorado River, from Lake Mead, Nevada, to Yuma, Arizona, with a key for identification. California Fish and Game. 38: 7-42.

Miller, R.R., and C.H. Lowe. 1967. Part 2. Fishes of Arizona, p 133-151, In: C.H. Lowe, ed. The Vertebrates of Arizona. University of Arizona Press. Tucson.

Sigler, W.F., and R.R. Miller. 1963. Fishes of Utah. Utah Department of Fish and Game, Salt Lake City, UT.

Sigler, W.F., and J.W. Sigler. 1987. Fishes of the Great Basin: a natural history. University of Nevada Press, Reno, NV.

Teuscher, D., and C. Luecke. 1996. Competition between kokanees and Utah chub in Flaming Gorge Reservoir, Utah-Wyoming. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 125(4):505-511.

Tilmant, J.T. 1999. Management of nonindigenous aquatic fish in the U.S. National Park System. National Park Service. 50 pp.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1997. Endangered and threatened species; Review of plant and animal taxa; Proposed Rule. Federal Register, 50 CFR 17. (September 19, 1997). 62(182):49397-49411. Washington, D.C.

Other Resources:

FishBase Summary

Author:

Pam Fuller, and Leo Nico

Revision Date: 8/5/2004

Peer Review Date: 8/5/2004

Citation Information:

Pam Fuller, and Leo Nico, 2026, Gila atraria (Girard, 1856): U.S. Geological Survey, Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville, FL, https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.aspx?SpeciesID=531, Revision Date: 8/5/2004, Peer Review Date: 8/5/2004, Access Date: 2/22/2026

This information is preliminary or provisional and is subject to revision. It is being provided to meet the need for timely best science. The information has not received final approval by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and is provided on the condition that neither the USGS nor the U.S. Government shall be held liable for any damages resulting from the authorized or unauthorized use of the information.