Craspedacusta sowerbii

(freshwater jellyfish)

Coelenterates-Hydrozoans

Exotic |

|

Common name: freshwater jellyfish

Synonyms and Other Names: peach blossom fish (China); Craspedacusta sowerbyi Lankester, 1880

Taxonomy: available through

www.itis.gov

Identification: Craspedacusta sowerbii is a hydrozoan (Phylum Cnidaria, Class Hydrozoa), which is most easily identified when it takes the form of a small, bell-shaped jellyfish, known as a hydromedusa. The hydromedusa measures about 5–25 mm in diameter, and is translucent with a whitish or greenish tinge (Peard, 2002; Pennak, 1989). It possesses five opaque-white canals, which form the gastrovascular cavity; four are radial and one is medially dorsoventral. Tentacles of varying lengths protrude from the upper margin of the velum, arranged with three to seven short tentacles between longer ones (Pennak, 1989; Slobodkin and Bossert, 1991). Freshwater jellyfish exhibit four very long tentacles, each parallel to a radial canal at the edge of the velum. Shorter tentacles facilitate feeding, while the longer ones give stability for swimming. The total number of tentacles varies from 50 to 500 (Pennak, 1989). Conspicuous swarms of hydromedusae appear sporadically, but are only one part of the animal's life cycle. Craspedacusta sowerbii more often exist as microscopic podocysts (dormant "resting bodies"), frustules (larvae produced asexually by budding), planulae (larvae produced sexually by the hydromedusae), or as sessile polyps, which attach to stable surfaces and can form colonies consisting of two to four individuals and measuring 5 to 8 mm (Angradi, 1998; Acker and Muscat, 1976; Pennak, 1989; Peard, 2002).

Size: hydromedusa is 5–25 mm in diameter

Native Range: Craspedacusta sowerbii is indigenous to the Yangtze River valley in China, where it can be found in both the upper and lower river valley (Slobodkin and Bossert, 1991).

|

Alaska |

Hawaii |

Puerto Rico &

Virgin Islands |

Guam Saipan |

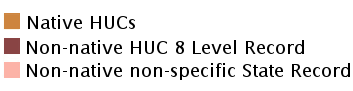

Hydrologic Unit Codes (HUCs) Explained

Interactive maps: Point Distribution Maps

Nonindigenous Occurrences:

Table 1. States with nonindigenous occurrences, the earliest and latest observations in each state, and the tally and names of HUCs with observations†. Names and dates are hyperlinked to their relevant specimen records. The list of references for all nonindigenous occurrences of Craspedacusta sowerbii are found here.

Table last updated 2/21/2026

† Populations may not be currently present.

Ecology: Craspedacusta sowerbii occupies a range of freshwater habitats. In its native range, it typically inhabits shallow pools along the Yangtze River, sometimes coexisting with a related species, C. sinensis, which occurs in the upper river valley (Slobodkin and Bossert, 1991). In this environment, changing conditions in the main river system expose jellyfish to fluctuating water levels, temperatures and plankton populations. Where it is introduced, C. sowerbii is most commonly found in shallow, slow moving or stagnant artificial water bodies such as ornamental ponds, reservoirs, gravel pits, and quarries (Pennak, 1956; DeVries, 1992; Peard, 2002). They prefer still or slow moving freshwater bodies of mesotrophic character between 12 and 33 degrees Celsius (Galarce et al., 2013). It has also been reported in large river systems, including the Allegheny, Ohio and Tennessee River systems, natural lakes, aquaria, and ornamental ponds (Beckett and Turanchik, 1980; DeVries, 1992; Peard, 2002). A study by Caputo et al. 2018, demonstrated that higher turbidity or increase in color of the water ‘‘brownification’’ would provide more favorable conditions for the invasion process of this hydroid.

Craspedacusta sowerbii is able to reproduce both sexually and asexually. Mature hydromedusae reproduce sexually by broadcasting gametes into the water. Fertilized eggs grow into ciliated planulae (larvae), which then settle and metamorphose into the polyp form. Polyps are capable of budding to produce hydromedusae, as well as either daughter polyps that remain attached to the parent, forming a colony, or frustule larvae which move to new locations before metamorphosing into new polyps (Pennak, 1989; Slobodkin and Bossert, 1991; Peard, 2002).

Hydromedusae are produced only sporadically, and a given location may go several years between blooms (Peard, 2002). Blooms are thought to be temperature dependent, requiring water of at least 25° C, and are most common in summer and fall (Kato and Hirabayashi, 1991; Dodson and Cooper, 1983; Anonymous, 1997; McGaffin, 1997; Peard, 2002). Other factors that may affect hydromedusa blooms include zooplankton populations, alkalinity, and calcium carbonate (Acker and Muscat, 1976; Koryak and Clancy, 1981; McCullough et al., 1981; Angradi, 1998). The more cold tolerant polyp form may have a wider distribution than the hydromedusa form, but because it is inconspicuous and easily overlooked, its range is difficult to determine (Kato and Hirabayashi, 1991; Angradi, 1998). Polyps overwinter by contracting into resting bodies called podocysts, which are essentially dormant cellular balls surrounded by a protective chitin-like membrane that allows them to withstand more extreme conditions than the active forms (Peard, 2002). When conditions are favorable, the podocysts grow into polyps again.

Like other cnidarians, C. sowerbii is an opportunistic predator, feeding on small organisms that come within its reach. A study in Northern Italy found that C. sowerbii feed on zooplankton with a preference for the Daphnia complex of species (Stefani et al., 2010). Both polyp and hydromedusa forms use nematocysts (stingers) to capture prey. Polyps are able to camouflage themselves by secreting a sticky mucous that adheres particles to their body (Pennak, 1989; Peard, 2002).

Means of Introduction: Initially, C. sowerbii was probably transported with ornamental aquatic plants, especially water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes), from its native region in China (Slobodkin and Bossert, 1991). An introduction at Fena Lake, Guam may have accompanied the introduction of tilapia following dam construction in 1952. The first sightings of C. sowerbii at Fena Lake were in 1970 (Belk and Hotaling, 1971). In the United States, polyps and resting bodies are probably translocated accidentally with stocked fish and aquatic plants or by waterfowl (Angradi, 1998; Wynett and Wynett, pers. comm. 1998). Pennak (1956) noted that new reservoirs and ponds (less than 40 years) exhibited the majority of hydromedusa blooms known at that time.

Status: Craspedacusta sowerbii is apparently established throughout most of the United States. Since the first record in 1880, it has been recorded in 44 states and the District of Columbia (Pennak, 1989; DeVries, 1992; Peard, 2002). In Colorado, only two populations have been reported, so the species may not be established there (Pennak, 1956; DeVries, 1992; Peard, 2009). The presence of C. sowerbii in Maui, Hawaii was confirmed in 1938, however its status in Hawaii is unknown. There have been no documented observations of C. sowerbii in Hawaii for at least 15 years (Edmondson, 1940; Eldredge, personal communication 2002).

Impact of Introduction: The impact of this widespread jellyfish is unclear. Dodson and Cooper (1983) proposed Craspedacusta sowerbii's preference for predatory zooplankton, such as the rotifer Asplanchna, could influence relative zooplankton species structure. Spadinger and Maier (1999) agreed with theorized affects on zooplankton communities finding that C. sowerbii hydromedusae prefer larger zooplankton (0.4–1.4 mm) and vigorous prey such as copepods. Under laboratory conditions and in 4 mm of water, C. sowerbii polyps apparently killed and fed on striped bass larvae (Dendy, 1978). Dumont (1994) speculated that C. sowerbii may consume fish eggs, but Spadinger and Maier (1999) note that it is generally not considered an important predator of eggs or small fish. Crayfish are considered the only important predator of the hydromedusa phase (Pennak, 1989; Slobodkin and Bossert, 1991).

References: (click for full references)

Acker, T.S., and A.M. Muscat. 1976. The ecology of Craspedacusta sowerbyi Lankester, a freshwater hydrozoan. American Midland Naturalist 95:323-336.

Angradi, T.R. 1998.Observations of freshwater jellyfish, Craspedacusta sowerbyi Lankester (Trachylina: Petasidae), in a West Virginia Reservoir. Brimleyana: The Journal of the North Carolina State Museum of Natural Sciences 25:35-42.

Anonymous. 1997. Freshwater jellyfish discovered in Idaho by Girl Scouts. Idaho Statesman. http://www.garf.org/freshjelly/html

Beckett, D.C., and E.J. Turanchik. 1980. Occurrence of the freshwater jellyfish Craspedacusta sowerbyi Lankester in the Ohio River. Ohio Journal of Science 32:323-324.

Belk, D., and D. Hotaling. 1971. Guam record of the freshwater medusa Craspedacusta sowerbyi. Micronesia 7:229-230.

Boulenger, C.L., and W.U. Flower. 1928. The Regents Park medusa Craspedacusta sowerbyi and its identity with C. (Microhydra) ryderi. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 66:1005-1015.

Caputo, L., P. Huovinen, R. Sommaruga, and I. Gomez. 2018. Water transparency affects the survival of the medusa stage of the invasive freshwater jellyfish Craspedacusta sowerbii. Hydrobiologia 817(1):179-191.

Deacon, J.E., and W.L. Haskell. 1967. Observations on the ecology of the freshwater jellyfish in Lake Mead, Nevada. American Midland Naturalist 78(1):155-166.

Dendy, J.S. 1978. Polyps of Craspedacusta sowerbyi as predators on young striped bass. The Progressive Fish-Culturist 40(1):5-6.

DeVries, D.R. 1992. The freshwater jellyfish Craspedacusta sowerbyi: a summary of its life history, ecology and distribution. Journal of Freshwater Ecology 7:7-16.

Dodson, S.I., and S.D. Cooper. 1983. Trophic relationships of the freshwater jellyfish Craspedacusta sowebyi Lankester 1880. Limnology and Oceanography 28(2):345-351.

Dumont, H.J. 1994. The distribution and ecology of the fresh- and brackish-water medusae of the world. Hydrobiologia 272:1-12.

Edmondson, C.H. 1940. Fresh-water jellyfish in Hawaii. Science 91(2361):313-314.

Eldredge, L.G. 1994. Perspectives in Aquatic Exotic Species Management in the South Pacific Islands. Vol. I. Introductions of commercially significant aquatic organisms to the Pacific Islands. South Pacific Commission, Noumea, New Caledonia. 127 pp.

Eldredge, L.G. 2002. Personal communication. Invertebrate Zoologist, Bishop Museum, 1525 Bernice Street, Honolulu, Hawai'i 96817.

Galarce, L.C., K.V. Riquelme, D.Y. Osman, and R. A. Fuentes. 2013. A new record of the non indigenous freshwater jellyfish Craspedacusta sowerbiiLankester, 1880 (Cnidaria) in Northern Patagonia (40° S, Chile). BioInvasions Records 2(4): 263-270

Guajaro, M.G., H.V. Sanchez, and Y. Salvador-Contreras. 1987. The first records of Craspedacusta sowerbyi Lankester for Nuevo Leon, NE of Mexico, and Cordylophora lacustria Allman for fresh water in Mexico. Collected at Presa Rodrigo Gomerza and Rio San Juan repectively. Publicaciones Biologica Facultad de Ciencias Biologicas Universidad Autonoma de Nuevo Leon 2(2):51-54.

Jankowski, T. 2004. Predation of freshwater jellyfish on Bosmina: the consequences for population dynamics, body size, and morphology. Hydrobiologia 530/531:521-528.

Jankowski, T., T. Strauss, and H.T. Ratte. 2005. Trophic interactions of the freshwater jellyfish Craspedacusta sowerbii. Journal of Plankton Research 27(8):811-823.

Kato, K.I., and S. Hirabayashi. 1991. Temperature condition initiating medusa bud formation and the mode of appearance in a freshwater hydroid, Craspedacusta sowerbyi. Zoological Science, Tokyo 8(6):1107.

Koryak, M., and P.J. Clancy. 1981. Craspedacusta sowerbyi Lankester (Hydrozoa) medusoid generation in two western Pennsylvania impoundments. Proceedings of the Pennsylvania Academy of Science 55:43-44.

Lankester, E.R. 1880. On a new jelly-fish of the order Trachomedusae, living in fresh water. Nature 22:147-148.

Ma, Xiping, and J. E. Purcell. "Temperature, Salinity, and Prey Effects on Polyp versus Medusa Bud Production by the Invasive Hydrozoan Moerisia Lyonsi." Marine Biology 147.1 (2005): 225-34. Web.

McCullough, J.D., M.F. Taylor, and J.L. Jones. 1981. The occurrence of the freshwater medusa Craspedacusta sowerbyi in Nacogdoches Reservoir, Texas and associated physical-chemical conditions. Texas Journal of Science 33:17-23.

McGaffin, P. 1997. Freshwater jellyfish found in lake. HeraldNet Local News.

Mills, E.L., J.H. Leach, J.T. Carlton, and C.L. Secor. 1993. Exotic species in the Great Lakes: a history of biotic crises and anthropogenic introductions. Journal of Great Lakes Research 19(1):1-54.

Moreno-Leon, M.A. 2007. Personal communication. Director General, Bufete Ambiental y de Negocios Del Noroeste SC.

Payne, F. 1924. A study of the freshwater medusae, Craspedacusta ryderi. Journal of Morphology 38:397-430.

Peard, T. 2002. Freshwater Jellyfish! Indiana University of Pennsylvania, Indiana, PA. 25 pp. http://www.jellyfish.iup.edu/

Pennak, R.W. 1956. The fresh-water jellyfish Craspedacusta in Colorado with some remarks on its ecology and morphological degeneration. Transactions of the American Microscopical Society 75:324-331.

Pennak, R.W. 1989. Coelentera. In: Fresh-water Invertebrates of the United States: Protozoa to Mollusca, 3rd edition. John Wiley & Sons, New York, pp. 110-127.

Rayner, N.A. 1988. First record of Craspedacusta sowerbyi Lankester (Cnidaria: Limnomedusae) from Africa. Hydrobiologia 162(1):73-78.

Sasaki, G. 1999. Sexual reproduction in freshwater jellyfish (Craspedacusta sowerbyi). Micscape Magazine, online at Microscopy-UK. http://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/mag/indexmag.html?http://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/mag/artdec99/fwjelly2.html

Slobodkin, L.B., and P.E. Bossert. 1991. The Freshwater Cnidaria or Coelenterates. In: Ecology and Classification of North American Freshwater Invertebrates. J.H. Thorp and A.P. Covich, eds. Academic Press, San Diego, pp. 135-136.

Smith, A.S., and J.E. Alexander. 2008. Potential effects of the freshwater jellyfish Craspedacusta sowerbii on zooplankton community abundance. Journal of Plankton Research 30(12):1323-1327.

Spadinger, R., and G. Maier. 1999. Prey selection and diel feeding of the freshwater jellyfish, Craspedacusta sowerbyi. Freshwater Biology 41:567-573.

Stefani, F., B. Leoni, A. Marieni, and L. Garibaldi. 2010. A new record of Craspedacusta sowerbii, Lankester 1880 (Cnidaria, Limnomedusae) in Northern Italy. Journal of Limnology 69(1):189-192.

Thorp, J.H., and A.P. Covich, eds. 1991. Ecology and Classification of North American Freshwater Invertebrates. Academic Press, San Diego. 911 p.

Wynett, C., and D. Wynett. 1998. Personal communication. Land owner, Switzerland County, IN.

Author:

McKercher, E., O; Connell, D., Fuller, P., Liebig, J., Larson, J., Makled, T.H., Fusaro, A., and Daniel, W.M.

Revision Date: 2/20/2024

Citation Information:

McKercher, E., O; Connell, D., Fuller, P., Liebig, J., Larson, J., Makled, T.H., Fusaro, A., and Daniel, W.M., 2026, Craspedacusta sowerbii Lankester, 1880: U.S. Geological Survey, Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville, FL, https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/factsheet.aspx?SpeciesID=1068&fbclid=IwAR3h09WLjym79-jGZtE2bRXjQPDm1oSlwJN3R771MSSS45mZUYfPVEDqoio, Revision Date: 2/20/2024, Access Date: 2/21/2026

This information is preliminary or provisional and is subject to revision. It is being provided to meet the need for timely best science. The information has not received final approval by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and is provided on the condition that neither the USGS nor the U.S. Government shall be held liable for any damages resulting from the authorized or unauthorized use of the information.